Epidemic of Hate in Lithuania: To Report, or Not to Report?

“Burn the faggots!”, “Kill them!” – said a flood of Facebook comments a few years ago on a picture of two young hay men kissing, which the couple had taken to celebrate the start of their relationship. “So you really were not trying to ‘hit on’ this person who attacked you?” – a gay Italian student, who was beaten near the night club in Vilnius, was asked by a pre-trial investigator.

“Skin these degenerates,” – a priest from Kaunas wrote online in response to a LGBT protest outside the Russian embassy in Vilnius. These are just a few of the more egregious examples of hate crimes and hate speech directed at members of the LGBT* community in Lithuania in recent years. Non-governmental organizations keep steadfastly repeating that Lithuania is facing a hate epidemic affecting not only the LGBT* community, but other socially marginalized groups as well. Law enforcement institutions, on the other hand, argue that they must treat all complainants equally, and official statistics do not show the large-scale prevalence of hate crimes in Lithuania.

European Court of Human Rights Investigates Inaction by Law Enforcement

According to official statistics supplied by the Information Technology and Communications Department about criminal offenses committed in Lithuania from January to September 2017, a total of 18 cases of incitement against a certain nationality, race, ethnicity, religion, or other social group (Article 170 of the Criminal Code) were registered. An interesting observation is that only two of the registered cases were taken to trial, while all other legal proceedings were terminated for various reasons. Official statistics do not show against which specific social groups these offenses occurred, but there is reason to suspect that a significant portion of the registered offenses were directed at LGBT* individuals.

Last year, the National LGBT* Rights Organization LGL performed an anonymous online survey of the Lithuanian LGBT community, attempting to determine on what scale members of the local LGBT* community encounter hate crimes and expressions of hate speech. The data collected was truly shocking: out of the 345 LGBT* individuals who responded to the survey, over half (54%) had faced instances of hate crimes and (or) hate speech in the previous year. Still more interesting was the fact that of those affected, only 13% reported the incidents to Lithuanian law enforcement. This suggests that instances of hate crimes and hate speech directed at LGBT* individuals are inherently a “latent” issue – that is, because these incidents are not reported to the appropriate institutions, they are not reflected in official statistics.

Even when these incidents are reported to law enforcement institutions, police, prosecutors and lawyers do not always respond in a constructive manner. For instance, national courts supported investigators’ and prosecutors’ decision to suspend pre-trial investigation of the aforementioned couple’s accumulated Facebook comments inciting homophobic violence, because “a person who has uploaded a photo of two men kissing to a public platform must know that this kind of eccentric behavior simply does not contribute to the promotion of tolerance and interpersonal understanding in a society with different views.” Refusing to accept the national courts’ decision, the couple submitted a complaint to the European Court of Human Rights, declaring that state institutions’ inaction toward the homophobic hate speech directed at them violates their right to respect for private life and constitutes discrimination on the grounds of their sexual orientation. In June 2017, the Strasbourg court took the decision to inform the Lithuanian government and begin examination of the case. A legal decision on the case can be expected in 2018.

Reporting Hate Crimes: a Cure for All Ills?

By encouraging individuals affected by hate crimes and (or) hate speech to report such incidents to law enforcement institutions, non-governmental organizations hope that they can make the scale of these crimes in Lithuania visible, combating this vicious circle of a problem. On one hand, it is obvious that without receiving reports about hate crimes and speech, law enforcement officials cannot improve their competency in responding to these types of incidents. Rising statistics in this area would also encourage state institutions to actively combat this negative upswing. But on the other hand, when non-governmental organizations turn victims over to police, investigators and lawyers, it is not always guaranteed that the investigation process will handle these individuals’ situations appropriately and in accordance with the victim’s specific needs. It is crucial to understand that people harmed by hate crimes are especially vulnerable due to their identity – that they were not attacked, whether with words or physical force, due to something they did, but because of who they are. What should be done in this situation? How do we solve this moral dilemma?

To their credit, in recent years, state institutions and law enforcement’s outlook on hate crimes and expressions of hate speech have progressed slightly. They are beginning to understand that the lack of statistics on the prevalence of hate crimes and hate speech does not necessarily reflect the real situation in the country – that these crimes usually go unreported. After a round table discussion between representatives of the Ministry of the Interior, Police Department, Prosecutor General, National Courts Administration and non-governmental organizations this June, the Ministry prepared a list of recommended measures for promoting effective responses by state institutions and law enforcement to instances of hate crimes and hate speech. This document accentuates the “latency” of hate crime and suggests measures for cooperating with non-governmental organizations representing the interests of socially marginalized groups in order to encourage members of these social groups to report instances of hate crimes and hate speech. On the other hand, it must be acknowledged that financial support is needed to implement these policies. European Union program funds could serve as a potential financial resource.

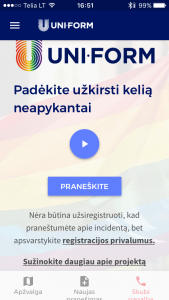

While state institutions and law enforcement slowly contemplate concrete steps they could take to combat hate crimes and expressions of hate speech, non-governmental organizations are taking their own steps, developing and implementing measures aimed at helping people affected by hate crimes and speech defend their rights. This autumn, LGL introduced the website and app UNI-FORM, designed specifically for reporting crimes targeting LGBT* individuals. Have you had any experiences where this website and app would come in handy?

While state institutions and law enforcement slowly contemplate concrete steps they could take to combat hate crimes and expressions of hate speech, non-governmental organizations are taking their own steps, developing and implementing measures aimed at helping people affected by hate crimes and speech defend their rights. This autumn, LGL introduced the website and app UNI-FORM, designed specifically for reporting crimes targeting LGBT* individuals. Have you had any experiences where this website and app would come in handy?

Report Now Using UNI-FORM Website and App

You can now quickly, safely and effectively report instances of hate crimes and (or) hate speech targeting LGBT individuals using UNI-FORM’s website or app. Whether you yourself have been the victim of such an incident, or just a witness, do not hesitate to report it using the UNI-FORM website or app. The website can be found at www.uni-form.eu, while the app is free to download online from Apple’s App Store or Google Play.

>>> UNI-FORM ONLINE PLATFORM CAN BE ACCESSED HERE <<<

Why do we recommend using UNI-FORM, rather than going directly to the police?[1] First of all, when filling out a report on the website or app, you will be given the opportunity to decide whether you want to submit it only to non-governmental organizations (such as LGL) for review, or to the police. If you decide to inform law enforcement, you will be asked to enter your contact information (telephone number and e-mail address). The good news in this event is that not only the police will be informed about the incident, but also a non-governmental organization to which you can turn with questions throughout every step of the investigation process. This will make it possible to perform further monitoring of hate crimes and hate speech in Lithuania. Second of all, if you decide to inform only a non-governmental organization, their representatives will be able to recommend emotional, psychological and legal support for you after reviewing the contents of your report. If you have been affected by LGBT-targeted hate crimes or hate speech, do not stay silent. We know how difficult it is and are here to help.

Reports can be submitted anonymously both through the website and the app, and does not require registering as a user in advance. If you do decide to register, however, you can keep track of your reporting history and submitted information and continue to update it, for example, as legal investigation is taking place.

The UNI-FORM website and app are currently available in nine European Union countries: Spain, Portugal, the United Kingdom, Malta, Hungary, Belgium, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. If you have witnessed or experienced hate crimes or hate speech against LGBT* individuals in any of these countries, the UNI-FORM website and app is available for your use whether you are travelling, working or studying abroad. Plans are underway to expand the UNI-FORM project to all EU member states.

The website and app are available in 10 languages, with Lithuanian, of course, among them. In order to make UNI-FORM accessible taking into account complexities of the other Baltic countries, the user interface is also available in Russian. This opens up the possibility for UNI-FORM’s future expansion to Eastern neighbors in the future. Working with LGBT* human rights activists and organizations in Belarus, LGL is studying opportunities to adapt UNI-FORM’s website and app for use in that country. Although directly reporting instances of hate crimes and hate speech targeting LGBT* individuals to Belarusian law enforcement does not currently appear feasible, taking this opportunity to compile reliable data about the scale of these incidents in Belarus would aid in the future development of evidence-based advocacy strategies in this critical area of human rights.

This comment was developed by the LGL’s Policy Coordinator (Human Rights) Tomas Vytautas Raskevičius.

This article is a result of the project “Sharing Expertise and Fostering LGBT Human Rights in Belarus.”

This article is a result of the project “Sharing Expertise and Fostering LGBT Human Rights in Belarus.”

[1] In case there is an immediate threat for your safety or well-being, please contact the law enforcement officers directly, while using the dial number 112.